Originally written for The Daily Star in January 2018. Read the original article here.

Of the many games released in 2017, ARK: Survival Evolved had arguably one of the most epic soundtracks of the bunch. Here, we discover the process that went into its creation.

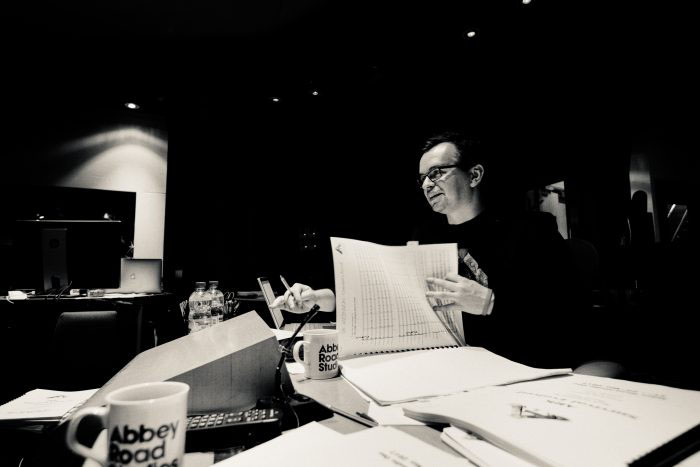

The work of British composer Gareth Coker, ARK boasts a sprawling, percussive soundscape that works both as a brilliant musical accompaniment to the game itself and a great standalone piece of work.

But, as many fans of the game will know, the soundtrack didn’t start out as a bombastic piece of orchestral composition.

Coker’s work effectively started out as musical sketches during the game’s early beta phase and it was only in May of 2017 that the score would go on to be developed, into a fully-fledged orchestral affair.

It was recorded at Abbey Road with the 93-piece London Philharmonic Orchestra ready for the game’s eventual launch in August.

I got the chance to see Coker in action recording the score and recently caught up with him to reflect on a busy year that also saw him making a surprise appearance at E3 to promote the long-awaited Xbox One sequel to Ori and the Blind Forest, currently titled Ori and the Will of the Wisps.

2017 was quite a busy year for you, wasn’t it?

It’s the life of being a composer. If only it was as easy as just pressing the ‘Distribute’ button and watching the sales roll in… It doesn’t work like that, unfortunately.

I think it’s probably fair to say that ARK was no small undertaking, isn’t it?

Yeah. It was such a gargantuan project that I didn’t really know what to expect, to be honest. That orchestra was 93 players. The most I had recorded with before that was sixty.

And just the sheer amount of music… How have you found the reception to ARK?

It seems to have been received better than I expected. With the whole early access thing, the game has been out for two years in the public domain already, so I wondered how much of a fresh splash the music could have made, but it does appear to have done that, so it’s a very pleasant surprise.

What did the game use before the full release? You had been working on the game for two years before the recording process, hadn’t you?

Yes. So I started working on it in April 2015 – basically a month after Ori and the Blind Forest came out, actually. And the main theme that I pitched is the main theme that’s in the game today, so that’s kind of cool.

Then, in the initial release, which was June 2015, there was the main theme, combat music for daytime, combat music for nighttime and transition music that told you what time of day it was and that was the case for about a year and a half.

Then, in February 2017, I added a bunch more music in to the game, but these were still digital mock-ups… We also had a light mix and a full mix, because obviously you don’t want that super epic music playing when you’re fighting… an ant, because that is literally what was happening for the first year and a half.

We had just the two pieces of combat music and it would be this really busy loud music and you’re fighting the completely insignificant creature, so it was a little bit ridiculous, but that is the nature of being in early access.

What kind of feedback would the fans give you?

One thing I found that is really unique is, because people had been hearing that combat music for one and a half years, when we changed it, I think there was pushback from the community.

And it’s not because they didn’t like the new music. It’s because they weren’t used to it anymore and they had good memories of the game with the battle music that had played prior, so in a way I guess I realised that I was messing with people’s nostalgia… On a film, where you’re working with a director, they might have fallen in love with a temp track.

With the early access, you’re not dealing with a director who’s fallen in love with a temp track. We’re dealing with the audience that’s fallen in love with the temp track. I don’t think that’s a phenomenon that can come up in any other medium.

So what did the briefing process from Wildcard entail? Were there any particular reference points that they wanted you to work with, or was it more freeform than that?

In general, working with Wildcard has been pretty awesome. They’ve given me a lot of creative freedom.

On the initial briefing, they were quite specific that they didn’t want it to sound like Jurassic Park…They wanted something that when the player fires up the game, they’d be able to immediately realise it’s ARK and nothing else.

So where do you start with that? You have to start with the theme… From that, we basically built the foundation of the entire score.

They wanted a signature that was recognisable without being a traditional melody. It could have been a sound effect or a texture, or something like that…

So basically the brief was, “You can do whatever you want, so long as it feels epic and fits with the island and so long as there’s a signature. The rest is up to you.”

There are a lot of systems in place in a game like this that change the way a player hears the music in-game. How daunting is it to finally hand those pieces over and leave them at the mercy of the player, essentially?

Well, with this game it’s unique. With single player games I’m very hands-on, but with multiplayer games it’s a little bit different – especially with open world sandbox games.

You couldn’t get much bigger than that kind of scope. You kind of hand it over and hope for the best, but one of the advantages of early access is you hand it over and maybe it works, but you can get feedback from the community and then you can always tweak it.

Because we have a large player-base it means we can get feedback a lot more quickly.

There’s something very melodic about some of these compositions, even when things are getting incredibly bombastic.

It’s amazing what happens when you add a melody on top of an action sequence. It can really tie everything together and give the player something to latch on to, rather than just being bombarded with noise the whole time… With action music, you’re just trying to give the audience something of interest.

I feel that a lot of action films make the mistake that when you dial everything up to 11 for the whole time then that can feel like nothing. When everything is epic, nothing is epic and vice versa.

How would you characterise your experience of recording at Abbey Road?

It’s like I told the orchestra on day one, getting ready to go out and introduce myself… The fifteen minutes before you do cue one, take one is absolutely terrifying.

First of all, you’re thinking about how much money has been spent on it. And 93 of London’s finest players at Abbey Road is about as expensive as it gets. [Laughs]…

Then you’re thinking about all the work to get to this point. It’s two years of my life condensed in to three days… And then, of course, there’s the Abbey Road pedigree.

You think of all those soundtracks that have been recorded in that room and Studio 2 and who was next door – only The Beatles… And it was the first time in my life where I was like, “Wow. I’m the least experience person here. What am I doing here?”

It was the first time that I’d had imposter’s syndrome. I’d never had that before. I’m usually pretty confident, but it was just that moment, just waiting for the recording to start… Once I’d introduced myself to the orchestra things calmed down, but to say I was overwhelmed briefly would be very accurate.

So once you’d finished at Abbey Road, you headed back to LA and surprised everyone at e3 with the Ori and the Will of the Wisps live reveal. How long did the post-production phase take? Where did that take place?

So while I was rehearsing and prepping for Ori and the live performance at E3, I was also mixing the score for ARK. They were both happening at the same time. I was sleeping at my mixing engineer’s house because it was 90 minutes away from me and I didn’t want to spend three hours driving.

We could save time and get more done… So we mixed the entire soundtrack, which is 125 minutes of music in eight days, which is a reasonably fast pace.

I would sit with my mix engineer, Steve Kempster for as much of the mix session as I could, but especially the first two days when we’re trying to establish what the sound of the whole score was going to be.

After that it’s a lot easier for everything to fall in to place. I think he was mixing one of the last few tracks when I was appearing on stage at e3… That three-week period at the end of May and the beginning of June was probably the busiest period in my career so far, but hey, we got through it and it turned out pretty well.

And I’ve got to say, congratulations on that E3 appearance.

[Laughs] I kept that one pretty quiet.

No. I didn’t even tell my parents. I just told my parents to watch e3 and that’s all I said. They were the ones who bought me piano lessons, so for them it was kind of like the whole thing was coming full circle, I think.

But yeah, we started working on that trailer back in February and it was a very difficult trailer to do because there are only five shots and most e3 trailers are 500 shots, so how do you tell a story when you’ve only got five shots and get people interested in the game?

Once the trailer had been locked, Eric Greenberg, the head of marketing at Microsoft said, “Yeah, let’s get a piano on stage.”

What was the brief from Microsoft?

The one thing that we insisted on was that it was about the video and not me being on stage. So we had me intro it and then it’s the video for 95% of the time after that, and I think that worked really well… I think it was ten minutes before I went on that someone said to me how many people were watching and it was something crazy like ten million, or something like that.

I mean, a lot of people watch the streams. The YouTube view numbers are meaningless because the actual stream numbers are what count.

So I was like, “Well, thanks for telling me that.”

Yeah, that doesn’t add to the pressure at all.

Once everything starts, you get tunnel vision and zone everything out… The way I was brought on to stage was I was rotated on, because they didn’t want me walking on… and it’s rotating for what seems like an eternity.

The audience gradually comes in to view and I’m like, “Okay, don’t make eye contact with anyone and you’ll be okay…” I think it took about twenty seconds to rotate, but it just felt like the longest twenty seconds of my life and I’m like, “This is crazy. If I mess up, this is going to be all over the Internet forever.”

And the gaming community is pretty brutal about these sorts of things, as I’m sure you’re aware… It was a bizarre, crazy couple of weeks.

I’m not sure how I’m going to top that, but I’m going to try. Maybe, one day, I’ll do a world tour like Hans Zimmer, but I’ll need to write more music.