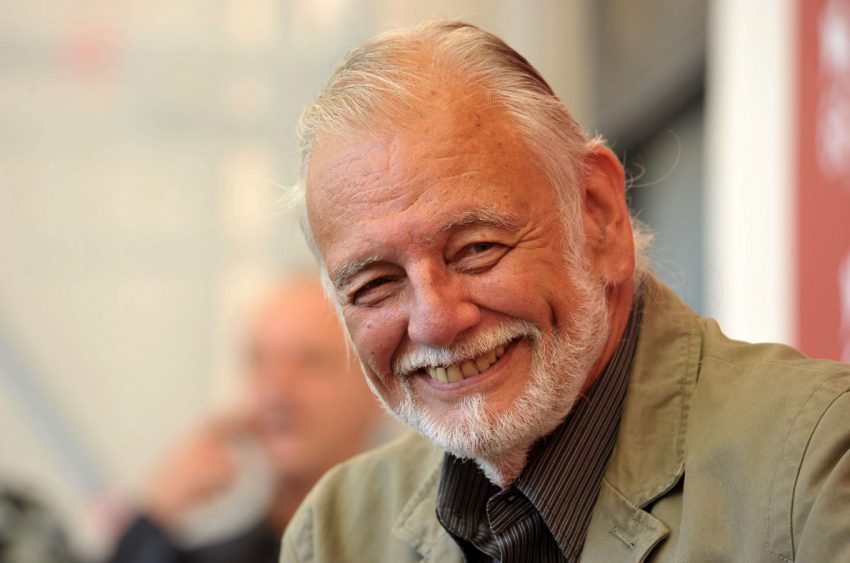

Having popularised the zombie genre almost single-handedly, it isn’t much of a stretch to describe George A. Romero as an icon that transcends legend. His signature thick-rimmed specs, silver goatee and charismatic smile hardly betray the fact that this is the man responsible for crafting some of the most shocking images in film history, but for a director who cut his teeth pioneering such an enduring trend, the popularity of the undead remains something of a mystery. “Especially now!” he laughs. “I don’t know why people are drawn to them, but I think the zombie became popular because of video games, more than anything else.”

It’s been nearly a quarter of a century since Night Of The Living Dead first shocked audiences with its striking blend of gore and subversive satire. Frequently imitated, but never bettered, he followed it ten years later with Dawn Of The Dead – arguably his magnum opus. Much has since been made of the socio-political themes prevalent in his work, but while his affection for zombies hasn’t exactly waned in the intervening years, their transformation from shuffling pallbearers of social commentary to a generic horror trope has been a concern. “I think it’s the way they’re being used now,” he says. “You can take zombies and use them to tell any story that you want to tell, and tell it in a world that is post-apocalyptic and post-zombie apocalyptic, but I don’t think anybody’s interested now.”

If he seems jaded by the success of the monsters he helped create, it isn’t without good cause. It’s been nearly four years since his last offering, Survival Of The Dead, was met with a lukewarm critical reception. All three of his original Dead films have been remade over the course of the past two decades, with varying levels of success. Having unwittingly spawned a wave of imitations from directors such as Lucio Fulci over the course of 70s and 80s, most of which passed him by at the time, Romero feels that many filmmakers today have lost sight of horror’s innate ability to impart social commentary. “I think that most people are just in it for the wrong reasons. It’s largely because the studios and finance people don’t understand it. They will tell you ‘I don’t know how to make a comedy, but I can tell you exactly how to make a horror movie,’” he states in a mock studio exec’s voice. “That’s what these guys think. They think you get a guy, you put a mask on him, give him a knife and you’re out of there.”

Is there a formula for horror? “There shouldn’t be, particularly if you want to put some politics in it, or a little satire, or do something else with it. Take World War Z. Max Brooks’ book was a little more political in that he was actually focusing on the way different countries behave and the way they speak to each other. But the film didn’t do that at all. I mean it sort of touches on Korea, but not in any way that’s meaningful. It’s just basically a video game.”

The comparison seems appropriate. Even Romero himself has his own affiliation with the format that goes back to the 1990s, when he directed a live-action promo for Capcom to promote the release of Resident Evil 2. An adaptation of the games themselves was set to follow suit, before it was nixed in favour of Paul W.S. Anderson’s much maligned effort years later. “We had a script that we thought was dynamite,” he explains. “Everybody loved it, except this one guy that makes all the decisions. And he had no idea what a video game was. He just had an impression of what he wanted the thing to be. So that was it.”

Romero’s output may have slowed in recent years, but his work continues to resonate. With the increasing return to the use of practical effects in favour of CGI in recent years, the work of special effects guru Tom Savini remains textbook for many. “You could see him developing,” he says. “Those effects on Day Of The Dead are pretty much unequalled in terms of zombie movies.” Also onboard was Savini’s protégé, Greg Nicotero, whose company, KNB Efx, now works on some of today’s most high profile practical effects, including The Walking Dead. He was a contact that proved essential when he returned to the genre for the first time in two decades. “This is the God’s truth, they wanted somebody that had assets,” he laughs. “When we did Land Of The Dead, Greg did those effects. They wouldn’t let me use Tom, because they couldn’t sue Tom in case it didn’t work out. That’s their kind of crass mentality.”

With the market saturated and Romero disillusioned by the studio system, today he opts to take a back seat. “I’ve always been sort of off in my corner doing my thing,” he ponders. “And I’ve just hit the point where I can’t do that anymore, you know? I used to be the only guy working with zombies, except for guys like Fulci. I sort of had that as my domain there for a while. And now they’re all over the place. They’re on broadcast television!”

Does he resent the dead’s current creative malaise? “It doesn’t really bother me,” he says with a wry smile. “I’m happy that I was able to do what I’ve done and I hope, maybe, to be able to do a little more, but I’m happy with that. What’s gratifying to me is that even when some of my films haven’t been well received they sort of grow on people over time. Take Knightriders – nobody saw it and for some people it’s one of their favourite films. Creepshow was recently re-released too, so they stick around and find new audiences. That’s gratifying.”

This interview was originally conducted for Film4 in November 2013. The original post can be found here.