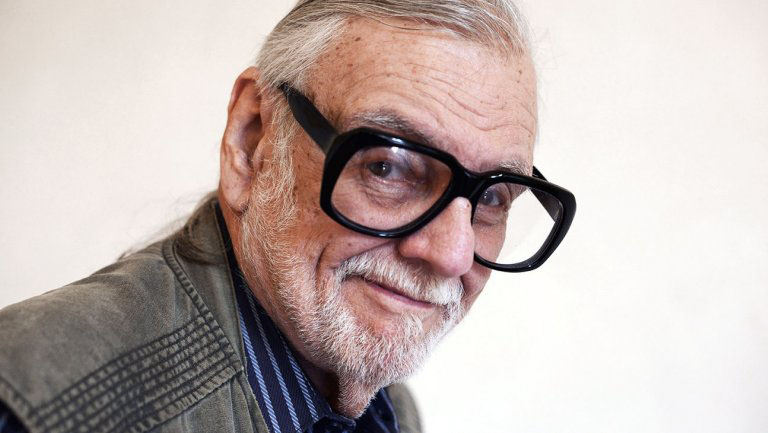

Whenever a great creative talent passes, there’s a tendency to lean on hyperbole when reflecting on their body of work. In the case of someone like George A. Romero, it’s virtually impossible to overstate their impact.

Put simply, without Romero, the horror landscape we know and love today simply would not be. With his passing on July 16th 2017, the world of cinema lost one of its greatest visionaries. I, like many others, lost one of my heroes.

Back in November 2013 I was lucky enough to get to spend some time with Romero when he visited London for an on-stage Q&A session at the BFI Southbank. The following interview served as the basis for a piece written for Film4, but in light of his passing, I thought the transcript warranted sharing in its entirety.

–

I may be misquoting you, but you said something a long time ago about how you’d warn first time filmmakers off making a zombie movie. Is this something you still feel today?

Well, especially now! [Laughs] Yeah, they’re taking over! Yeah, so many people… I don’t know why they’re drawn to them or why it… first of all, I think video games have popularised the zombie much more than films. Because, you know, really, the first film to gross a $100 million for a zombie movie was Zombieland, which was fairly recent. And the remake of Dawn did about $75 million, but anyway, it’s not the kind of numbers that Hollywood is going to rush to, thinking that this is going to be a trend. So I don’t know what happened, but I think the zombie became popular because of Resident Evil and because of House of the Dead and because of video games more than anything else.

It’s interesting to hear you say that, because your links with Capcom go back to the mid-90s when Resident Evil 2 came out. You shot an advert, which was aired in Japan, didn’t you?

Yeah, I shot a commercial.

What happened with regards to the feature film that was originally planned? I understand you wrote an original script that never came to fruition. The screenplay has circulated online for a while.

Yeah, I wrote a script and, you know, it’s funny. The guy who owned that company – Constantin was the company that wound up making Resident Evil and owned the rights. I had Capcom on my side and I had the executives from Constantin on my side. That’s who I was working with – the LA executives from Constantin and the Capcom guys themselves. And we had a script that we thought was dynamite and everybody loved it, except this one guy in Constantin that does everything and makes all the decisions, and that was it – this guy named Bernd Eichinger, who came in and said [in a German accent] “No, this is not what I want.” And that was it. And he had no idea what a video game was. This is the guy that made House of the Spirits and Das Boot and he just had an impression of what he wanted the thing to be, which sort of flew in the face of all of us – Capcom and his own guys. So that was it.

Video game spin offs and remakes have become the norm now. Do you feel that there’s a lack of creativity in horror now?

[Long pause]

[Laughs]. I think that there has always been a lack of creativity in horror, because I think that most people are just in it for the wrong reasons. I mean, I see very few films that seem to have an affection, or a real affection for the genre – Guillermo Del Toro, maybe. I haven’t seen The Descent, but I hear that that’s a good one. Let The Right One In. You can count them on one hand.

So there aren’t any contemporaries that you really feel are taking the mantle on?

Well, I don’t think, first of all… I wouldn’t see it that way anyway. But I just don’t find that there are a lot of people… and particularly it’s largely because the studios and finance people don’t understand it. It’s like they will tell you [in a mocking voice] “I don’t know how to make a comedy, but I can tell you exactly how to make a horror movie.” That’s what these guys think. They think “you get a guy, you put a mask on him, give him a knife and you’re out of there.”

There’s no simple formula.

No, there’s not. No. None. There shouldn’t be. And, particularly, if you want to put some politics in it, or a little satire, or do something else with it. Because, with my films – the zombie films anyway – the horror is just the surface personality. That’s it. But I like to think there’s something underneath all of them. There certainly was in my mind anyway.

Is that why you’ve made the move to comics now – to explore these themes further?

No! [laughs]. No, I’m just doing this because I’m sort of marking time. I have a zombie idea that I would love to do, but I don’t want to do it now. I could never do it now. I could never sell a two million dollar movie to anybody. Because right now, I would have to guarantee to spend at least $100 million or more. It’s just the way finance runs now. There actually is a company that we’ve worked with on both Diary and Survival that would do another film and we would have the same creative control, just as we did on those, but not right now, because it’s just too crowded, you know?

So, really, the Marvel thing is just… it’s sort of an idea that I had. It was actually sparked by… I was doing a talk show and somebody said “Well, here’s what you ought to do – put zombies and vampires together,” like a sort of Jason vs. Freddie. So then I started to think about that and got this idea for the sotry that I’m writing. And it’s fifteen books – I like the idea of a longer form and I like the idea of being able to just let it all hang out in terms of the fact that I don’t have to shoot it, so I can let my imagination run wild.

Have you spoken to Stephen King about it at all, because I understand that he’s a fan of the medium as well. Are you still in regular contact with him?

Not regular contact, no. I haven’t spoken to him recently, since he went off in to the world of theatre.

I wanted to ask about working with Tom Savini and Greg Nicotero. We’re seeing an increasing shift back towards practical effects now. When you were working on Dawn and Day, did you have any idea how influential their practical effects work would go on to be?

No! [laughs]. No, Tom was just… his hero was Lon Cheney and he just wanted to do the best work that he could. And you could see him developing, you can see his skills developing. I think, Day of the Dead, those effects are pretty much unequalled in terms of zombie movies. Greg has got this big company now and he’s a part of KNB. We still see each other. We just saw him recently. They were doing a big re-release of the music from Day of the Dead – a double disc vinyl, all the music that John [Harrison] recorded, not only the stuff that wound up in the film and so it’s just out. And I saw Greg at the screening and he was basically saying “Those were the days!” But he’s gone on to do… his credit’s on most of the big practical Hollywood stuff.

But, you know, I know for example, when we did Land of the Dead, Greg did those effects. They wouldn’t let me use Tom, because they couldn’t sue Tom. This is the God’s truth. They wanted somebody that had assets, [laughs] in case it didn’t work out – “we can get something back.” That’s the kind of crass mentality. So they wouldn’t let us use Tom. And so KNB, being a big company with a reputation to protect… Anyway, we were working with Greg on that and there’s one particular effect – this happened several times across the course of the production, but there’s one effect particularly that Greg said “This had to be practical. You can’t do this CG. It’s impossible.” And it’s this scene where somebody walks up to the corpse and it looks headless. And he leans forward and the head flops forward. And it’s still connected – the spinal chord apparently…

The science of zombies, eh?

[Big laugh] Yeah! “Oh, it’s still alive!” And so that effect of the head flopping forward – we tried and tried and tried. Greg tried everything. It always looked like a puppet. It always looked just a little too raw. It just didn’t have the right look. And so we wound up having to do it in CG. And it never really even looked the much better, but it looked a little better.

I think it’s still the scare that stands out for me in the film.

Is that right?

Yeah, and I’ve seen the film a lot. It still gets me every time.

Okay.

I’m not sure if anyone’s mentioned these to you, but when Lucio Fulci made…

[Laughs] Those…

Yeah, ‘those’ films… How strange was it for you to see those films riding on Dawn’s success? Dawn came out in ’78 and Zombie Flesh Eaters came along in ’79, I think.

I guess they came later. I don’t know. Had he not done one earlier?

I have a feeling he was making Zombie Flesh Eaters while you were working on Dawn of the Dead, or when Dawn was being released and a producer in Italy said something to him about tying the two films together.

Oh, maybe. Yeah. Didn’t they actually call it ‘Zombi’ over there?

Yeah and Fulci’s film was marketed as ‘Zombi 2’.

[Laughs]

Were you aware of this at the time?

No.

No?

No, and I wasn’t paying much attention to it at all. I was just happy that Dawn was successful. It originally opened in Italy. It played in Italy first and then Germany, I think. We didn’t get US distribution for quite a while, and so I was just happy when we got US distribution, which we got largely because of its success in Europe. So I didn’t pay attention to it and I didn’t go to see them. I’ve seen them since, of course, and I think they’re sort of fun. But I had no particular care or concern about it at all.

I’ve always been sort of off in my corner doing my thing. And I’ve just hit the point where I can’t do that anymore, you know? I can’t hide and just bring the zombies out. I used to be the only guy working with zombies, except for those guys, like Fulci. And that died quickly. And I was able to sort of keep going. I sort of had that as my domain there for a while. And now they’re all over the place. They’re on broadcast television! [Laughs]

Do you feel there are still socio-political stories that are worth telling with zombies now, or do you feel that they’ve just come to be another horror trope that gets rehashed time and time again?

I think that that’s the way they’re being used now. I think of course there are. Think about any story you might want to tell. You can do it with zombies. The financial collapse – how do you do that? Maybe there’s a little bit of that in Land, or at least the class/society idea, but I think you can use the zombies and take any story that you want to tell and tell it in a world that is post-apocalyptic and post-zombie apocalyptic. So I think, yeah, but I don’t think anybody’s interested now, I think. Even World War Z, which I think Max Brooks’ book was, to that extent, a little more political in that he was actually focusing on the way different countries behave and the way they speak to each other and the things that they hide and the things that they allow to made public. But the film didn’t do that at all. I mean it sort of touches on Korea and all that, but not in any way that’s meaningful. I think it’s just basically a video game.

Do you find it frustrating that the genre that you’re renowned for creating has ended up in the creative doldrums, or does it not really bother you?

It doesn’t really bother me. [Laughs] You know, I’m happy that I was able to do what I’ve done and I hope, maybe, to be able to do a little more, but I’m happy with that. I don’t know. Stephen King was often asked about how he felt about Hollywood ruining his books. And he said [quoting James M. Cain], “They’re not ruined. They’re still right there on the shelf.” And I guess that’s sort of the way I feel about my stuff, you know? My stuff is there, for good or bad, and it remains there. It has shelf life. What’s gratifying to me is that even when some of my films have been released and haven’t been well received they sort of grow on people over time. Knightriders – nobody saw it and for some people it’s one of their favourite films. I think Creepshow was recently re-released too. So they stick around and find new audiences. That’s gratifying.

–

George A. Romero

1940 – 2017