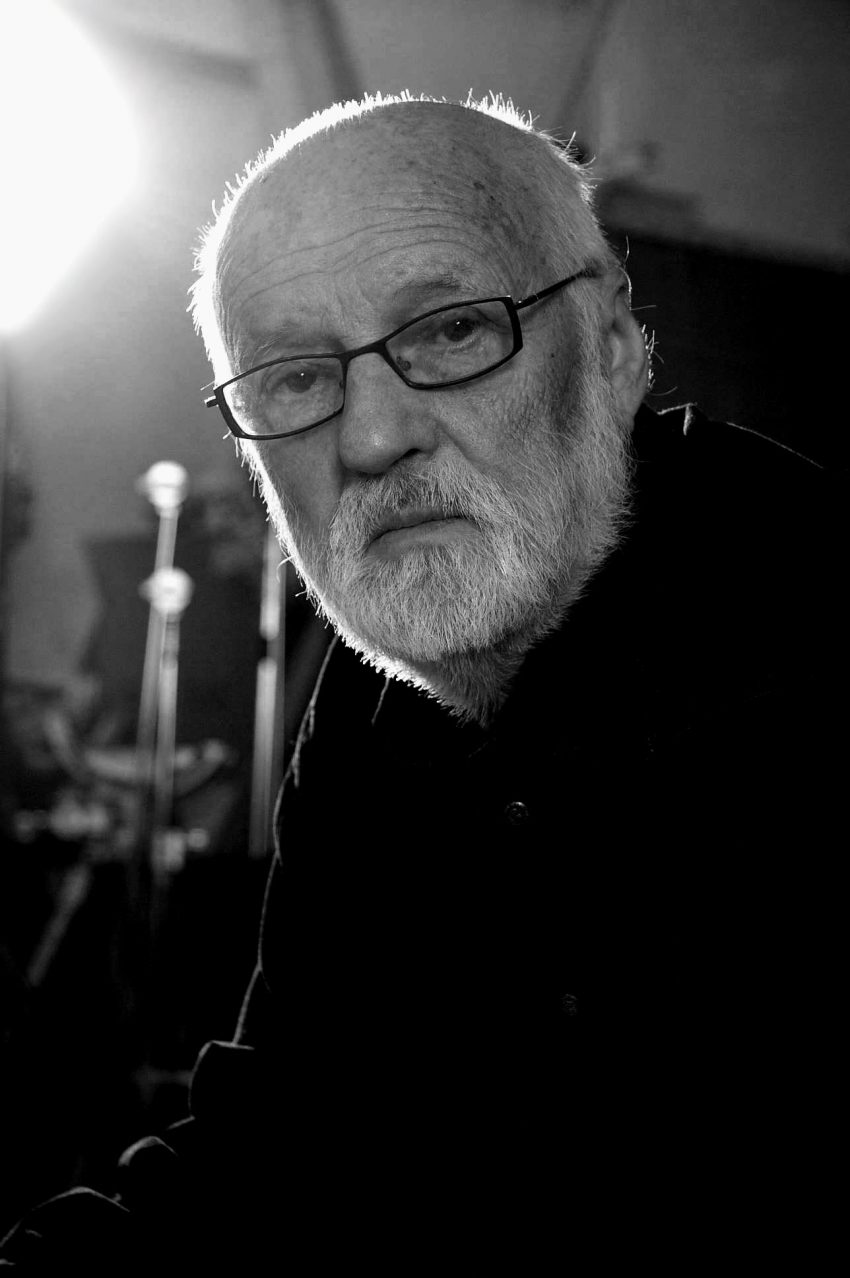

It’s probably fair to say that Jan Švankmajer is something of a luminary in the world of animation. Widely revered for his early animated short films and dark feature-length fairytales that combine surreal animation and live action, his latest project, Surviving Life, is a typically madcap endeavour that uses his inimitable visual style to focus on the loopy world of psychoanalysis. In a rare interview, I recently spoke to him about his inspiration, his affinity for dreams and what makes him tick.

How did Surviving Life come about?

For a long time now I have wanted to make a film that would illustrate André Breton’s idea about the ‘communicating vessels’ of dream and reality. Certainly, in all my films I have worked with dream logic that I combine with raw reality. However, I was missing an actual dream that would be mysterious enough to allow a consistent story to be developed from its interpretation. My collection of dreams – for I write down my dreams – still lacked such a dream. And then at last it came. Surviving Life derives from a dream of mine and the beginning of the film is the authentic dream itself. Indeed, psychoanalysis cannot be absent from such a film.

Is psychoanalysis something you’ve always been keen to explore in your films? In spite of the complex subject matter, this feels far lighter and much more accessible than some of your previous work, which was far darker in tone.

Besides psychic automatism, dream also serves as one of the journeys to our unconsciousness. I use both in all my creative work, not only my film work. No authentic, imaginative work can make do without these “excursions” into our unconsciousness. Psychoanalysis then, is one of those significant interpretation systems (similar, for example, to alchemy) that help us, at least partially, to orientate ourselves in the labyrinth of our unconscious.

Was this a conscious decision?

I do not think along those lines. Themes come to me the way they want. I always just realize them with the same urgency. It is a certain kind of auto-therapy. It is the process of liberating myself from outer as well as inner determinants.

Some people interpret your work as dark while others find a great amount of humour in your surreal imagery. Do you strive to strike a balance between both?

This whole civilization of ours balances on the edge of horror and the grotesque. I think that the genre of black comedy reflects our situation perhaps the most accurately.

Do you prefer working with a combination of live action and animation, or do you still have a preference for working primarily with stop motion? How much of that depends on the story?

A particular theme determines everything. I try to rationally intervene in this process as little as I can.

It’s been nearly 20 years since you last made a short film. Do you still have an affinity for the format or does your main interest lie in features now?

I would not attribute any significant meaning to the fact that I make features at the moment. I simply get ideas for features now. There is nothing more to it.

What inspires you?

I make imaginative films and every imaginative, creative work has rather traditional sources of inspiration: childhood, dream and eroticism. My case is no different from any other.

Tell us something you’re ashamed of.

I am not an exhibitionist.