Face to face with Hunter S. Thompson’s visionary collaborator…

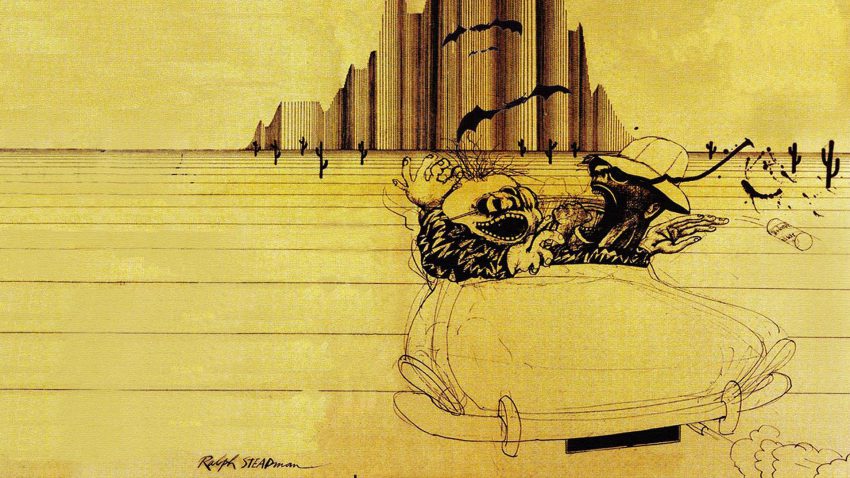

Painter, photographer and writer Ralph Steadman is a quintessential renaissance man. His work alongside gonzo visionary Hunter S. Thompson is justifiably the stuff of legend, and with a career spanning 50 years his work still represents perhaps some of the most iconic, radical and recognisable illustrations of the 20th century.

Filmed over the course of a decade, For No Good Reason charts the career of a true visionary. The result of a long-term project begun in the late-1980s by director Charlie Paul, who started out filming artists in their studios on 35mm film, the film came about when Paul contacted Steadman with a view to documenting his work.

“I had been a fan of Ralph’s art since first reading (Thompson’s) Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas when I was 14,” Paul explains. “Being a young punk, his anarchic message appealed to me. I contacted Ralph by letter to ask if I could come and meet him with the idea of filming him work. We must have clicked because I left his house after that first visit with a box of Ralph’s original old archive footage. I discovered he had given me personal footage to create the story of his life.”

Over the course of the next 10 years, Paul would join the artist for frequent filming sessions in which he would place the camera over Steadman’s work, and record his creative process as his distinctive ink marks developed in to full fledged artworks.

“Charlie kept turning up with this camera, so I started posing eloquently and saying smart-ass things to him,” Steadman jokes. Regardless of intent, the end result offers a profoundly fascinating snapshot of a body of work that remains unparalleled, not least because of its connection to the writing of a timeless American icon.

The first of many pairings, Steadman initially accompanied Hunter S. Thompson (pictured, above, with Edward his bird) on assignment to cover the Kentucky Derby in 1970. The resulting article, the seminal The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent And Depraved, birthed what would come to be known as gonzo journalism. A literary movement was born and a fruitful partnership was launched that would endure until Hunter’s untimely passing at his own hand in February 2005.

“What I discovered in the process was how intrinsic Ralph was to Hunter’s writing,” Paul muses. “In those early classics in which they were paired; The Kentucky Derby, America’s Cup, The Curse Of Lono, Hunter used Ralph to reflect his observations in the American way of life. What I found most challenging during all my years of visiting was the time around Hunter’s death. Ralph struggled deeply with his grief and it took some time for him to adjust to his loss.”

Paul’s film touches on the love/hate nature of Thompson and Steadman’s relationship, put perhaps the most fascinating aspect is its revelation of just how disparate the duo’s personalities really were, with Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner going so far as to suggest that Thompson himself felt Steadman was even crazier than he was. “That is purely Jann’s opinion,” Steadman protests in jest. “I am painfully sane!”

After many years spent documenting Steadman in his studio and conducting interviews with various friends and collaborators, it became apparent to Paul that the film should be structured much like the experience of his visits to Ralph, in which his life seemed to unfold through his stories. It was at this point in the process that mutual friend Johnny Depp was brought in.

“The editing process was in phases over three years, and as the shape began to take hold I knew the film needed a conduit between Ralph and the audience,” Paul explains. “Johnny was the natural choice. They met through Hunter and have an existing rapport from their times spent together over the years at (Hunter’s house) Owl Farm. I had the structure of lead stories by the time we filmed with Johnny. He was brilliant at keeping these on track as Ralph has a tendency to take conversation off-piste in surprising directions.”

While his gonzo output remains arguably his best-known work, equally fascinating is the mark Steadman has left elsewhere in the cult landscape. Be it his work with William S. Burroughs, which saw the great American writer blasting holes in his work with a shotgun, or the warped Polaroid images that featured in the pages of Richard E. Grant’s autobiography, Steadman’s output remains as fascinating as it is varied.

Case in point, his work on the poster for cult favourite Withnail & I, which has adorned the walls of many a likeminded connoisseur of cake and fine wine over the past 30 years. Directed by Bruce Robinson, who would later come to play a part in Thompson’s legacy himself by directing the film adaptation of The Rum Diary in 2011, Steadman’s involvement stemmed from a drunken visit from the young director.

“Bruce arrived at our house one day with a pal of his and they had both been drinking,” Steadman recalls. “I asked Bruce if he would like to see our 500-year-old Horse Chestnut Tree. He fell down underneath it and proclaimed: ‘It’s not your tree, Ralph! It’s everybody’s tree!’ Bless his heart. He is right, though.”

Now aged 78, Steadman continues to find inspiration, although he self-deprecatingly concedes that “boredom” plays a large part in his output today. “And curiosity,” he adds. “What exists on that blank sheet of fine paper?”

As the film draws to a conclusion, a brief interview segment is shown in which Steadman wistfully writes himself off as a “visual polluter”. I ask for clarification.

“I am joking,” he retorts, as expected. “I wouldn’t know what else to do, except write, which I also do. Hunter said to me, ‘Don’t write, Ralph! You’ll bring shame on your family.’ But we are all polluters – visually and lavatorially.”

A version of this interview was originally published on the Clash website and can be found here.