Originally written for Films On Wax in May 2015. Read the original article here.

Three decades in the making, it’s no small relief that George Miller’s triumphant return to the Mad Max franchise arrived with a definitive bang and with the long awaited Fury Road, currently tearing up the box office with its explosive action set pieces, it’s only fitting that we turn our attention to the music that has helped bring Miller’s dirty dystopian world to life once more.

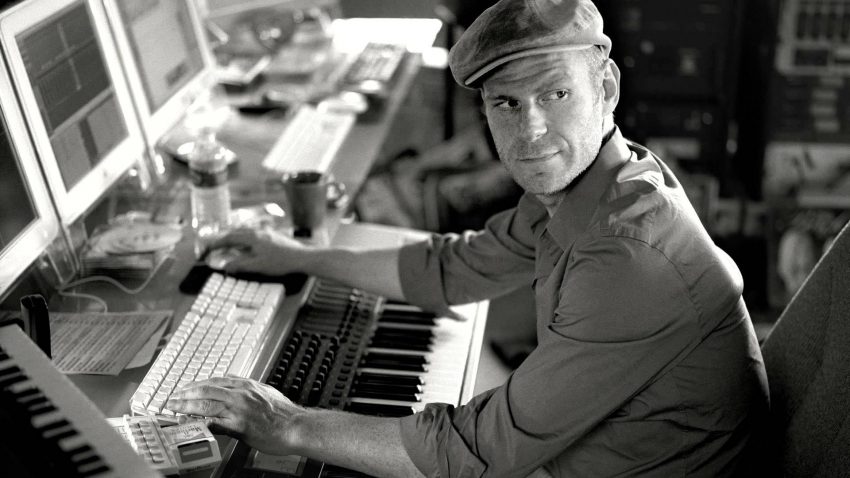

Scored by the ineffably charming Tom Holkenborg (aka Junkie XL), Fury Road’s blend of brash soundscapes and affecting orchestration is the perfect accompaniment to one of the most exciting action blockbusters of the year thus far. Paul Weedon recently caught up with the man behind the madness to talk about his work on the film, his relationship with Warner Bros. and the importance of a budding composer leaving their ego at the door.

–

Congratulations on the film, Tom. It’s great to see how well it’s been received. Talk me through what your jumping off point is when you’re presented with such striking material.

Well, the most important thing is, when I got involved in this project, which was over two years ago – I worked on it with George for 18-20 months almost with some very intense preparation – the first thing… when I saw the film, it didn’t have the beginning or the end, but it had the whole chase sequence and when I saw it I was like: “Oh, man. We really need to step it up here.” And, for me, when I spoke to George, he was like “well, what did you think” and I said, “well, it’s an amazing film” and he said, “well, what should we do?”

And I that we needed this over-the-top, big rock opera, with every aspect that comes with it; like choir, guitars, drums, big symphonic strings, big brass, but we also need to have these really intimate moments where we go really small in scoring, sound design, instrument settings, and we need all of that for this film. And when I saw the film, the opening shot was actually the drummers on the truck, with a guitar player in front of it. So that was the first scene I saw and it was burned in to my memory. So when I got back I really wanted to attack that scene and that setting before I moved on.

And I understand your first interaction with George came about just as you were finishing work on 300: Rise Of An Empire, right?

Yeah, that’s correct. I got a call from Darren Higman, who’s the Vice President of Warner Bros’ music department and he said “what are you doing tonight?” and I said, “well I’m just wrapping up this thing and going home to have dinner with my wife” and he said “no, you’re not. You’re going to be on a plane to Sydney.”

And it wasn’t clear to me what was going on at that point and then he said “yeah, I want you to meet George Miller” and then it hit me like a heart attack. I was like “holy shit, is he talking about Fury Road” [laughs]

It’s a term that’s bounded around an awful lot, but George Miller really is a legend. You don’t expect to hear his name bounded around in a conversation like that, so that must have been an interesting call to receive.

Yeah, he is. And he’s such a nice person, y’know?

It’s funny. I’ve never met him, but to watch interviews and hear George talk, he seems like this really gentle soul, who just happens to make these really bold, brash films. It seems like he’s able to mask this kind of rage inside him – with the exception of the Happy Feet films, obviously.

[Laughs] Yeah, what’s interesting about that point… when you hear George and I talk, we’re both these very jolly people. We always have this great outlook on life and a great energy towards any problem. Anything can be tackled. Nothing is a struggle. But then, deep inside, we have that really dark side in our personality that comes out, with him, in the filmmaking, and for me in making music.

And your relationship with Warner Bros. has clearly been very important to your career. How helpful is it to have that kind of shorthand with a studio? Obviously, you end up working with lots of different directors, but it must be great to have the Vice President putting you forward in situations like that.

Well, to have a very good relationship with a studio is very, very important. Not only for the flow of income, but also to get notified beforehand on what projects might come up and that you might be suitable for as a composer. And it started, actually when I met Darren Higman and Paul Broucek, who’s the President there in the early 2000s when I made my first trips to Los Angeles, not to do a gig – but to meet with these people and explore the possibility of becoming a film composer. And I understood from that point that I can’t just walk in to Los Angeles and say “I want to do a film”. I had to learn it from the ground up and I decided to take that opportunity.

And it was interesting that in the year I had a Number One hit with my Elvis remix in multiple countries… at the same time I was being an assistant to Harry Gregson-Williams, just chopping up audio files in the basement. And I just knew that I had to learn this from watching other composers work – trying to assist him and learn all the aspects that are important in film scoring. And throughout those years, meeting with all the studios and collaborating with other artists and film composers… at a certain point I started collaborating with Hans [Zimmer]. We worked on The Dark Knight Rises and that’s when I met all the Warner Bros. people again. It was like “hey, how are you doing?” And I was like “I’m doing great, I’m helping Hans out with this film” and then after that I did Man of Steel and Man of Steel was directed by Zack Snyder, who then asked me to join and do 300. And that was the first film I did on my own as a composer for Warner Bros. And because of that it went all very rapidly.

George Miller heard of me and then Jaume Collet-Serra heard of me and Scott Cooper heard of me for Black Mass, which is the new Johnny Depp film with Benedict Cumberbatch about the life of Whitey Bulger. So all these people started hearing about me and my work and they wanted to work with me. So it’s invaluable to have a relationship like that with a studio.

Famously, Fury Road went through a lengthy production process. Having initially seen this middle cut, which at the time I understand was around three hours long, how did you go about tackling this knowing that there was still material to be shot?

Um, well, it’s interesting when you see a film in that early stage, or even more so to read the script before you see the movie, and when it’s such early days, you build up all kinds of ideas that sometimes later are not useful, or sometimes become very, very useful. Some of your initial ideas of what a movie might be or what a person could be, or a character or an event could be might be grounded and based on reading the script or seeing a very rough cut of it with not even a beginning or an end. It was an intense collaboration with George… I mean, eventually I ended up in Sydney for eleven weeks with my family, with my music editors, with my assistants, with my whole studio packed up in flight cases sent out, to really sit down every day from morning until really late at night to get it right. To get the details rights. And it was a remarkable process.

How much of the soundtrack is live composition and electronic composition? I know you made extensive use of engines and other sounds. It has a very experimental feel to it, in a way.

Well most of it is a really weird blend of things. The concept of the film, from George’s point of view, was that all the things that you see in the picture are things that were meant to be something else, but they were repurposed from something else. So the cars are multiple combinations of different cars, all the weapons that they use are just things from other objects in the past, but they’re now repurposed to become a weapon. You see a lot of things like that in the film. So the music is actually kind of similar. So you hear a lot of things that sound like strings but they’re actually not strings. They’re other instruments that have the function of strings. There are live strings in there, actually quite a lot, and there’s live brass and there’s choirs and I made my own music boxes in there for live recording. There’s a lot of percussion in there that I played myself. Obviously live guitars. Synthesizers. Bass guitars. Piano. But there’s also a lot of sound design and instruments that were created out of animal noises, metal objects that are being hit with chains and baseball bats and fifty gallon oil drums that were thrown down the studio and we’d record every aspect of it. And sound design was done of that and it turns in to perfect instruments – very eerie drums that are very high or sometimes they even bring melodic information that you would use.

It sounds like it was a very fun process.

Oh, it was. By far. I mean if you work for 18 months with a lovely director like George, you not only become colleagues, but you become friends. You become best friends. And then when you wake up on the day the film comes out and everyone is sending you emails saying “have you read this review?” and I’m just like “what happened last night?” And I’m going through Rotten Tomatoes to find that it’s 100% fresh based on 30 reviews. I’m just like, you’ve got to be kidding me. That’s the most beautiful gift that you can wish your best friend gets.

It’s a dream.

[Laughs] It is.

Tonally, I know it’s very different, but did you refer back to Brian May’s work on the first two films at all?

No, I did not actually. And the reason why is that George was very specific about it. He wanted to create something new for this film and not revisit older themes, because the world is different. It’s more gruesome. It’s more serious. And Max is a really different character in this. In the older films there’s a lot of tongue-in-cheek and, yes, he did lose his wife and his kid, but he wasn’t as dark as he is right now. I mean, chronologically, you could almost say this film fits perfectly after Beyond Thunderdome because many years have passed where he got captured, he got tortured, he escaped, he saw people die around him, he tried to save people but he couldn’t save them. So he’s a very troubled character in this one with post-traumatic stress and his memory constantly comes to haunt him and it takes a good while in to the film before you get to know this character and also warm up to him. He feels very dangerous and unpredictable in the first three quarters of it.

You said in another interview that you left your ego at the door when it came to entering film scoring. How important was it to go back to learning the ropes?

Well it’s very important. For me, at least, it’s very important. I feel that if I knew this 25 years ago I would have pursued a career in film scoring right away, but obviously I didn’t. But if I look back, the craft that you need to become a successful film composer is so much more than being an artist. You need to be a team player. You need to be a great manager. You need to be a great communicator. You need to be able to take a lot of criticism and you need to be able to take that criticism in and make something beautiful out of it instead of becoming sombre and bitter and unproductive. And the work stress is extremely high. The time pressure is extreme on some of these projects and it’s not for everybody. But I’ve felt it’s really for me and I feel like a fish in water when it comes to film composing, film scoring and the challenges that come with it. But especially collaborating – most of the directors that I’ve met are such lovely and intelligent people and it’s amazing to thrive off their knowledge and their energy.

I know that you’re a big user of social media. How valuable and important is it for you to have that contact with your fans?

No, it is very important and I find it great to communicate with these people and talk about what they think and what they feel and you do that automatically when you’re an artist, you know? Say you’ve done a show and then you hang out at the bar and you talk to people about the set and it’s like “I thought this track was great, that track was great,” or people would say “I saw you last year at Glastonbury and I liked you so much more this year, or Leeds” and it’s great to have those conversations.

Tom, thanks for your time.

No, thank you so much.